Economics

36 degrees 30

minutes

The American Civil War was an issue of economics. Slavery became an intensely debated issue in the early 1800s because of the division of land and labor. The invention of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney in 1793 had fueled America's Industrial Revolution. A technological invention that saved time and labor, the cotton gin actually fueled rapid expansion of various markets, goods and services. Additional slaves were then needed to bring more cotton to market and more land was sought for planting. New shipping ports were developed, and older ports were improved and expanded. Manufacturing plants, particularly in the North and overseas in England, had expanded their production in order to process the cotton and make fabric.

The varied economic resources of the North—industrial, commercial, financial, agricultural—gave the North an enormous advantage over the predominantly agricultural South. When the war began, the North had 92 percent of the nation's industries and almost all of the known supplies of coal, iron, copper, and other metals. The North also owned most of the nation's gold, which could be used to buy war materials abroad, whereas the Confederate wealth was largely in land and slaves.

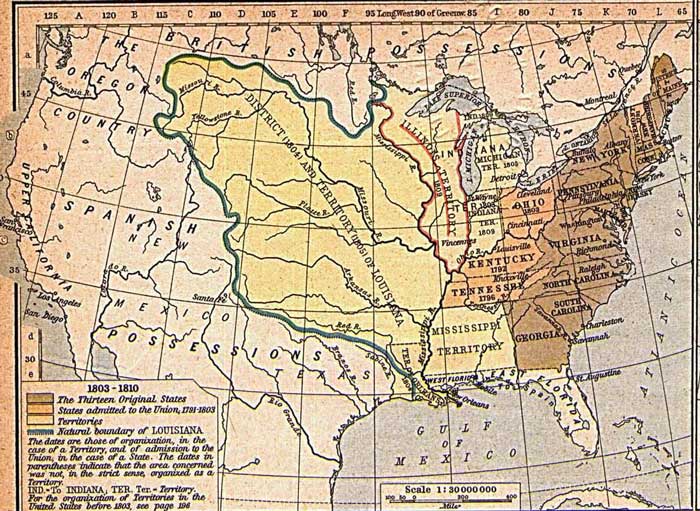

The Louisiana Purchase—western lands purchased from France in 1803 by President Thomas Jefferson shown in light yellow color on the map below—opened up much of the land between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains for exploration and settlement. The amount of land more than doubled the then United States. The lands in the Southern states had become over-farmed and fallow; so, the newly acquired Louisiana lands were also agriculturally attractive. Farmers brought with them slave labor to harvest their crops.

As territories grew economically, they were ready for statehood. As Congress was composed of representatives from states, the balance of power could be changed when a territory was given statehood. Because slave labor was needed to continue national as well as personal economical expansion, Congress then used slavery as a pawn in a strategy for admitting states to the United States.

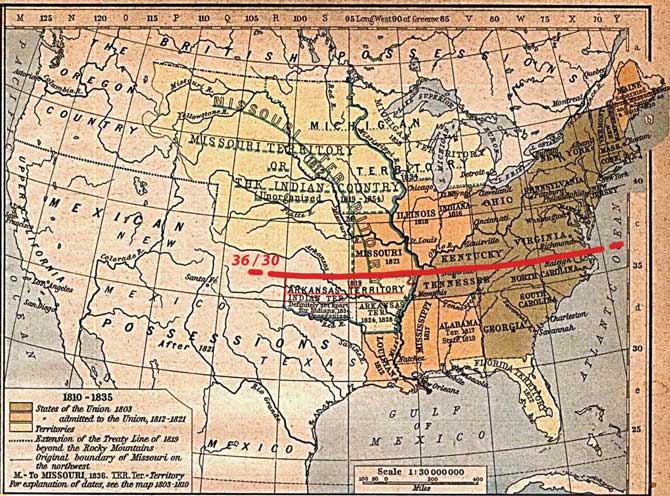

In particular, Missouri, a slave state, petitioned for statehood; however, Congress fiercely debated the issue wanting to equalize the number of slave states with non-slave states. As a result, giving statehood to Missouri provided an excuse to also allow statehood to Maine as a free state. The law that allowed Missouri and Maine statehood at the same time was called the Missouri Compromise of 1820, thus keeping a balance of the number free and slave-holding states (see map below).

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 designated the latitude, 36 degrees 30 minutes, as being a dividing line—slavery was allowed below the line, but not above. Missouri, Kentucky and Virginia were then slave states located above the line; however, the rest of the Louisiana Purchase lands were closed to slavery.

The

Missouri Compromise began to break down around 1849. In 1848 the United

States won the war with Mexico and gained additional western lands, in

particular, the territories of Texas and California. The population of

Texas increased with settlers needing new land for farming and animal

grazing, and California's population exploded because of the Gold Rush

in 1849.

In 1850 California petitioned for statehood as a free state. Since no other states were ready to petition for statehood, Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, known as the "Great Compromiser" and "Great Pacificator," and Daniel Webster, senator from Massachusetts and whose last name is usually associated with dictionaries, applied the philosophical idea, popular sovereignty, so the inhabitants in other former Mexican lands would decide the slavery issue for themselves. This would appease the both pro-and anti-slavery coalitions. This compromise was known as the Compromise of 1850.

Also in 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act was enacted, maintaining that slaves were property; it allowed for runaway slaves in one state to be returned to their owners in another state, even in the Northern states. Northerners were not amused with the Slave Act, however, the events of 1850 seemed momentarily to appeal the Southern states.

The tranquility was short-lived because the slavery issue was rekindled with the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, a controversial bill introduced by Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas; it undid the 1850 Compromise, promoted westward expansion and accelerated the beginning of the Civil War. Slave-holders saw the fertile lands in the Kansas and Nebraska territories as more promising for crop production than the arid lands further west, but as border territories, many residents were also abolitionists. These areas had been closed to slavery expansion, but now popular sovereignty allowed the citizens to decide for themselves.

Stephen A. Douglas, a noted orator nicknamed the Little Giant, debated the political newcomer, Abraham Lincoln, in a series of debates for the U. S. Senate in 1858 now known as the Lincoln-Douglas Debates. Although Douglas won the election for the Illinois senate seat, Lincoln became noted for his oratory style and positions. When Lincoln became a presidential candidate of the newly formed Republican Party, Douglas, the Democratic Party candidate, again opposed Lincoln.

Extremist abolitionist factions, like John Brown and sons, fought equally avid supporters of slavery. A great amount of bloodshed ensued over the slavery issues for which Kansas became known as "Bleeding Kansas." John Brown attempted to capture a federal small-arms arsenal in Harpers Ferry October 16, 1859. At that time Harpers Ferry was a part of Virginia. The raid was stopped by federal troops commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee, who later would become commander of the Confederate Army. Though Brown was hanged for treason, northerners were sympathetic, and to some, he was a martyr.

Return to the top of Economics, or follow the links below>>

Share this site with your friends and associates using this link!