Matthew Brady

—from New York City to

the battlefields as war photographer!

Matthew Brady became widely known for Civil War photography documentation. Before the war, Brady had studied in New York with Samuel Morse, a painter, daguerreotypist and later inventor of the telegraph. Within a few years, Brady had his own studio.

Initially, Matthew Brady focused on portraiture of famous Americans, but when the war started, he invested a lot of money in photographic equipment, chemicals, and employees in order to photograph the war on the battlefield.

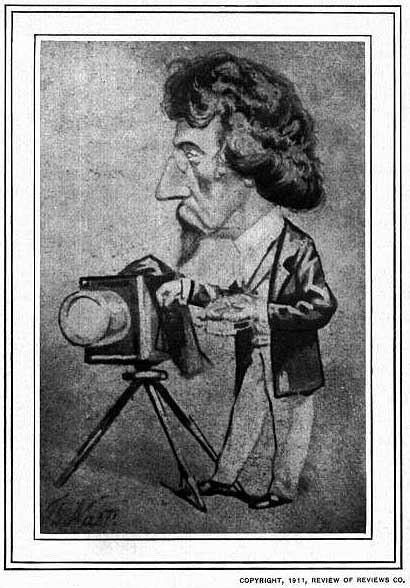

Thomas Nast drawing of Matthew Brady

On the battlefield

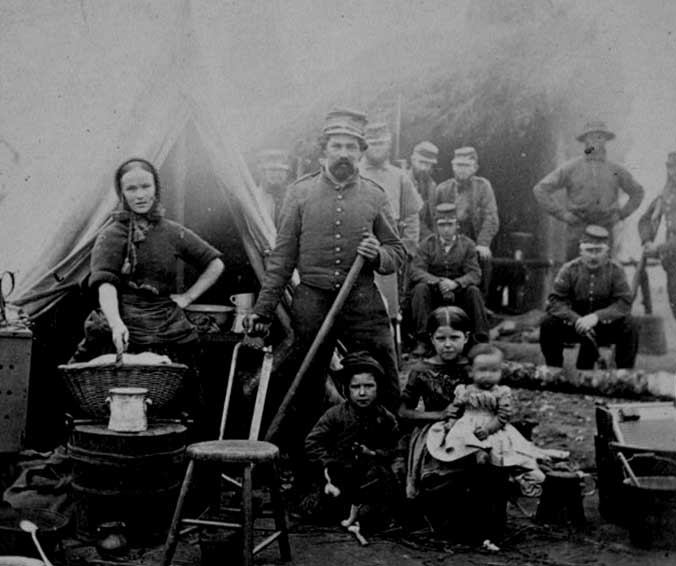

Camp of 31st Pennsylvania infantry near Washington, DC, by Brady, which shows a family in a soldier's camp, an occurrence that was somewhat common. |

Brady captured these Union soldiers for a pose with their highly reliable and accurate 3-inch Ordnance Rifle. |

Photographing the war was not an easy endeavor. Photographers carried extremely hazardous chemicals and hundreds of glass plates in wagons over uneven roads and rocky terrain and coped with large, cumbersome cameras. In addition, they were exposed to sharpshooters!

Photographic Processes

The daguerreotype photograph was produced by having a positive image projected directly onto a copper plate coated with silver. It needed to be angled to be seen, sometimes seeing the negative image, then the positive. They also were very delicate surfaces and needed separation and cover protection when store. The daguerreotype, the dominant form of photography until the 1850s, was superseded by tintypes. Tintypes were very popular during Civil War times because they were cheaper and more easily carried by soldiers. They were produced using the wet-plate method of photography.

Another process, the wet-plate or collodion, was done by first coating or sensitizing the photo plate surface with collodion, a flammable, light-sensitive syrupy solution; then, put into the camera and exposed to light. After taking the picture, the photographer had to develop the negative exposure within five minutes. The wet-plate process preserved every detail as long as the subject stood still for a time. Tintypes used a japanned iron plate coated with collodion. Glass plates were also used to produce clean, sharp photographs.

Before the Union Army arrived at Fredericksburg, Brady's activities were described as follows: "No sooner had Brady placed his queer looking cameras in position than he and his assistants became the target for hundreds of rifles, but he calmly proceeded with his work and in accordance with his usual luck secured his pictures and returned uninjured." (Miller)

Gettysburg photograph by Timothy O'Sullivan, July 1863. Photos like this brought the horror of war to far away cities and into homes.

The Civil War was the first war to be photographed almost in its entirety. The camera became a powerful media tool because the war was experienced through raw, real-life images, which contrasted to artists’ interpretations that appeared in Civil War newspapers, notably Harper’s Weekly, the New York Tribune, or Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper.

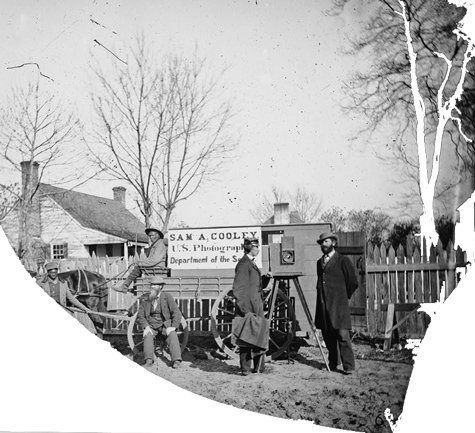

Wagons and camera of Sam A. Cooley

Both sides had photographers —for example, Matthew Brady and Timothy O'Sullivan in the North and A.D. Lytle, George S. Cook in the South. However, few southern photographs exist, perhaps because war photographs were unpopular. Also, many Confederate Army negatives were lost through fire or breakage or simply destroyed after the war, perhaps in order to erase the memories.

Of the southern photographs, those from George Cook are the most vivid. Cook had managed Brady's New York gallery for a time before the war. Cook's photographs are maintained by the The Valentine Richmond History Center, Richmond, Virginia.

Brady after the war

Matthew Brady, nicknamed "Mr. Lincoln's Camera Man," too thousands of photos during the Civil War. He suffered financially when the government did not buy his negatives after the war. Though Congress voted him recompense of $25,000, it was not enough to cover his expenses. His negatives were used as payment to debtors, and in subsequent years, Brady was poor and almost forgotten. He died in 1896.

Some of his negatives were later found in an attic and immediately recognized for their documentary and qualitative value; others were accumulated from all over the country. His photographs provide an unmatched historical record of the time of the 1850s and 1860s.

Now his genius is recognized and his photographs are considered paramount documentation of the Civil War times; many of Brady’s photographs can be seen in the print and photographic collection of the Library of Congress.

Return to top of Matthew Brady, or follow the links below...

Share this site with your friends and associates using this link!