Plantation Life

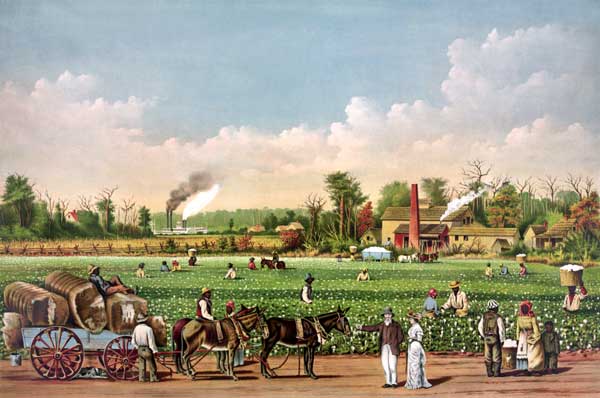

Cotton plantation on the Mississippi, Currier and Ives, 1884

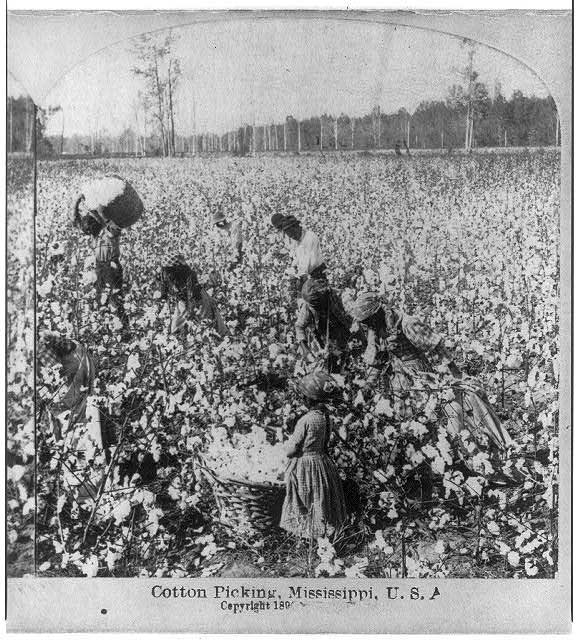

By 1860 out of a population in the South of about 12 million, slaves accounted for roughly one third, or 4 million. Cotton had become king, replacing tobacco, sugar cane, and rice as major money making crops. Many southerners had come to believe that slavery was not only necessary but also profitable. To be sure, only a small percentage of the southerners owned slaves, but the slave owners were the wealthiest, in general the best educated, and the most influential men in the South. As the years passed and larger areas of the South were planted in cotton, slaves became increasingly numerous and valuable.

Plantation life may have (not) been enticing,

depending on your position and perspective. The structure of a plantation consisted of a simple structure whereby an owner, planter or farmer, had power over his holdings, whether it was land or people, that is slaves he had bought at auction.

Social Groups

Owner, aka Planter—

Travelers who journeyed through the South in the 1850s occasionally passed an imposing mansion set well back from the road with close-clipped lawns sweeping down to a river. The house itself, shaded by tall trees and surrounded by formal gardens, looked cool and inviting with its wide verandas and its white Grecian pillars supporting the roof.

Many of these mansions, often having twelve or fifteen luxuriously furnished rooms, were places of distinction and beauty. These were the homes of the wealthy planters, who might have from 100 to 500 slaves or more. However, fewer than 2500 such planters, even as late as 1860, could afford exorbitant luxury.

|

|

A contrast of styles. The Roublieu Jones House (left), Natchez, Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, has been repaired and opened as a historic structure. Note that the living area of the house is raised up to protect it from flooding. On the other hand, the antebellum plantation (right) in Greene County, Georgia, has been left to decay, but still illustrates the grandeur inherent in some plantation mansions.

|

The less wealthy planter lived well but in more modest circumstances and owned from 20 to 100 slaves. These were the most influential people in the South and in 1860 numbered fewer than 50,000. His home might have as many as eight or ten rooms, with wide halls and deep verandas surrounding by spacious, shaded grounds. The furnishings of a home of this type were usually comfortable but not luxurious because most of the planter's wealth was tied up in land and slaves; he could not afford to import expensive household goods. |

Plantation-house where the Wray family lived for generations. A cotton plantation of 2700 acres employing fifty tenant families in 1918 and seven tenant families, Greene County, Georgia, c. 1937 |

There were also many small independent farmers who owned several acres of productive land and who lived much like small farmers in other parts of the country. They lived in rudely constructed but reasonable comfortable frame houses, considerably better than the one-room log shelters of the poor whites in the pine barrens and in the mountains. Each year they sold a bale or two of cotton as a cash crop. Their food came largely from the corn, potato, and vegetable patches around their houses. They were almost self-sufficient and had in addition a small case income of perhaps $100 or more a year. Some, of course, owned more land and were fairly prosperous. Some of the small farmers who prospered were able to buy a slave or two, or perhaps a slave family.

A really prosperous small farmer might have 8 to 10 slaves. He continued, often, to work in the fields, shoulder-to-shoulder with his newly purchased slaves. Although he increased his income a couple of hundred dollars a year, he remained distinctly separated from the large wealthy planters as well as the poor whites.

When the planter was not away from home on public business, his life was comfortable but not easy. An endless number of details engaged his attention to keep the plantation running. In addition to supervising the work on the plantation itself, the planter had to keep records of his business transactions, usually in terms of letters to ship-owners and bankers and to agents who sold his cotton to the northern and overseas textile mills. The planter was not a rich man in terms of money in the bank. He shipped his cotton in care of an agent in the north or England, instructing him to sell the cotton and ship back agricultural implements, clothing, books, and household furnishings. Frequently, after his cotton was sold and his purchases were made, he was in debt to the agent who handled his business for him on commission.

Plantation Overseer—

The treatment of slaves on plantations where the owner was frequently absent and where an overseer was in charge was likely to be the most severe. It was hard to secure men who were willing to serve as overseers, and some of those who did become overseers were harsh, brutal men. On the other hand, death of even a single slave meant a serious financial loss; illness of a slave was a setback. Any illness or injury resulting from ill treatment was contrary to the planter's interests. To protect his investment, therefore, the planters were apt to keep his slaves adequately fed, clothed, and housed.

Plantation Slaves—

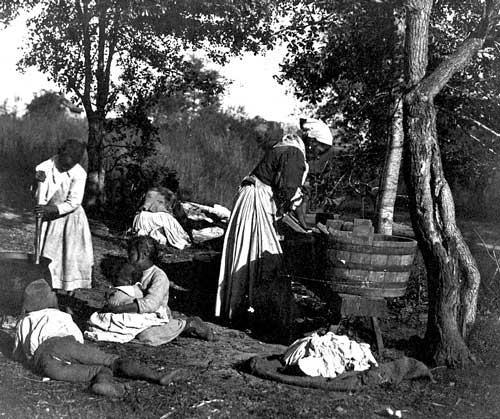

Plantation wash day by R. Eickemeyer, c. 1887 |

Even more time-consuming was the day-by-day routine of managing the plantation. Each morning the slaves had to be assigned to particular jobs—tending the cotton, hoeing corn, cultivating other food crops, cutting wood, hauling water, feeding livestock, and doing household chores. Many worked in the homes of the planters, cooking the meals, doing the housekeeping, and tending the children. |

On large plantations the slaves usually worked in gangs under the management of an overseer, whose job it was to get as much work out of the labor force and as big crops as possible. Some slaves became skilled workers. Women learned to spin, weave, and sew; some became cooks, maids, laundresses, dairymaids, and nurses. Men became blacksmiths, painters, jewelers, and silversmiths. A few learned carpentry and bricklaying, though only a few were allowed to build a house.

Community Groups

Free Negroes—

Free Negroes were for the most part former slaves who had been set free by

their owners. Some, of course, were people who had never known slavery because

they were children of free Negroes.

By 1860 there were about 250,000 free Negroes; they

were largely located in Virginia and in the large cities of the South. After a slave uprising in Virginia in 1831, a

variety of laws restricting the movements and privileges of free Negroes were

passed. For example, they could not testify in court, post bond, or learn to

read or write.

The word Negro was adopted from Spanish and Portuguese and first recorded from the mid 16th century. It was the name of a dark-skinned group of peoples originally native to Africa south of the Sahara who were the target of slave traders. It remained the standard term throughout the 17th–19th centuries and was used by such prominent black American campaigners as W.E.B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington in the early 20th century. Since the Black Power movement of the 1960s, however, when the term black was favored as the term to express racial pride, Negro has dropped out of favor and now seems out of date or even offensive in both U.S. and British English. The term is used here to put website language into a historical context. (e-dictionary, 2014)

Laborers and Tenants—

In the southern agricultural economy there were also a large number of white farm laborers and tenant farmers. The farm laborers were hired during the harvest season or, in some instances, to do work regarded as too dangerous for the expensive slaves. The tenant farmers rented and tilled fields that were usually worn out from overuse. These tenant farmers were generally in debt to the planter or to the crossroads storekeeper.

Poor Whites—

The "poor white" group of southerners, which probably was not more than 10 or 12 percent of the white population, was looked down on by other whites and called, in different parts of the South, "hillbillies," "crackers," or "piney woods folks." For the most part, they lived in log cabins. Their standard of living was low, at least in part because they lived on the poorer soils, called "pine barrens," or along the rugged Appalachian mountainsides and other hilly area that were hard to cultivate. They often suffered from poor health, but they had pride and a fierce independence. In some cases, they were employed to work along side of the plantation owner's slaves in the cotton fields.

Return to the top of Plantation Life, or follow the links below...

Share this site with your friends and associates using this link!